C.A.C : Can you tell us something about your artistic journey? What led you to devote yourself entirely to painting?

R.W : I come from a working-class background. My father was a plumber, my mother a nurse. My parents moved to West Berlin with my brother and me in the early 1970s. They had a strong class consciousness, which is why art and culture beyond pop culture were rather decried as bourgeois and not very present at home. My childhood was very difficult; my father was a heavy alcoholic and died young from drug abuse. I was 14 years old at the time. I often felt the need to escape, and painting and drawing were my means of choice. I also gained a certain amount of recognition for my craftsmanship and imagination at an early age. However, my family did not provide me with much cultural or social capital, so for a long time I was unaware that it could also be my career path. Until then, I had been thinking more in terms of applied arts: graphic design or architecture. The idea of fine art only developed towards the end of my school days, when I showed my work to an emeritus professor, a friend the mother of a friend, and he pointed out that it could also be an option for me. Being quite naive and lacking any cultural sophistication at the time, I naturally had no idea what kind of taste was necessary for discourse at art school, so I had to apply six times before I was admitted to study art. I filled the waiting period by studying philosophy (which I didn’t really understand at the time) and political science. So I was already in my mid-twenties and very skilled technically when I finally began studying art. At art school, I discovered oil painting, which I immediately fell in love with, even though painting was extremely out of fashion in the nineties. I tried out a lot of things, working my way through the only German representatives of painting who were also recognized within the art academy, which was infected with conceptual art: Gerhard Richter and Martin Kippenberger. I learned about art history and discourse, about my strengths and weaknesses, and also how to position myself in the context of my fellow students and contemporary art. By the end of my studies, I was already painting reduced but very realistic pictures of singular objects, which I was later able to use to convince gallerists. But that took a whole ten years, during which I kept myself and eventually my family afloat with various jobs and occasional sales, more badly than well. For twenty years, since Berlin gallerist Michael Haas discovered my work at an off-fair in the then-booming Berlin, I have been living exclusively from art. Today, I work with several international galleries, but I still don’t feel quite where I see myself and my paintings. The pressure to be economically successful is sometimes motivating and sometimes annoying. But it may also be because I’m not willing to pay any price for my career. I care for my health and resist the supposed constraints of the cultural industry a little by putting only a relatively small number of handmade “products” on the market. The time I take for myself is my luxury. For me, living a good life means being able to paint. As long as I can do that and my family doesn’t have to starve, I feel very privileged.

C.A.C : How do you experience the influence of Berlin, where you live and work, on your artistic practice?

R.W : I moved to West Berlin, which was then divided by the Berlin Wall, with my parents when I was three years old. This city was and is charged with history. Political awareness is deeply rooted here, and political education in school was very intensive and vivid because of this situation. I stayed here, on the one hand, because the Wall fell shortly after I graduated from high school, and it would have been stupid to leave the city at such an exciting time. On the other hand, it was also cheaper here than anywhere else—and for the reasons mentioned above, I hardly had the financial means for alternatives, especially not abroad. There was no money in Berlin in the nineties, but there was plenty of space to experiment. When I was studying art, Berlin was an El Dorado for all kinds of art forms. Everything mixed together because no one knew where they were headed, and almost every spontaneous art event in some catacomb or gray backyard also had a party vibe. In these gothic spaces, art was inevitably installation-based and had the underground techno or hip-hop soundtrack of its time. The connection to music, the existential, and even the debates about postmodernism at that time and in that place had a profound impact on me, even though I continued to paint in a somewhat academic style and had to clearly define and fight for my niche in this environment. Staying here was more of a blessing for me: suddenly there were hardly any Berliners around me, but many new perspectives from all over the world were added, so I didn’t have to jet around the world all the time to acquire them, which I couldn’t have afforded anyway. The discourses in this city continue to this day and are very diverse. L’Art pour l’Art and the art market, although the latter has certainly gained in importance due to the sharp rise in general costs, are only areas of a broad intellectual discourse in a wide-ranging cultural system. In this city, one thing leads to another, and the insistence on the freedom of art is traditionally interpreted here as a political gesture.

I still enjoy the fact that there are countless artists of all stripes here, and that there are still spaces where we can meet, independent of the vanities of the art market, and sometimes organize exhibitions together. My studio is part of a large factory complex in the north of the city center. Very often, I sit there with my colleagues in the garden with a good cup of coffee and we talk about art, God, and the world without separating the two. Since I do rather introverted work, these natural and barrier-free contacts and options in Berlin’s broad scene are all the more important as a counterbalance, also because they offer me a constant mirror through which I can locate myself, personally and artistically.

C.A.C : Could you describe your creative process, from selecting a theme to completing the final work? How do you find inspiration in your daily life? Do you follow your intuition, or do you work according to a conceptual logic? How has your work developed in recent years? Can you tell us more about the technique you use? Do you always work with oil paint?

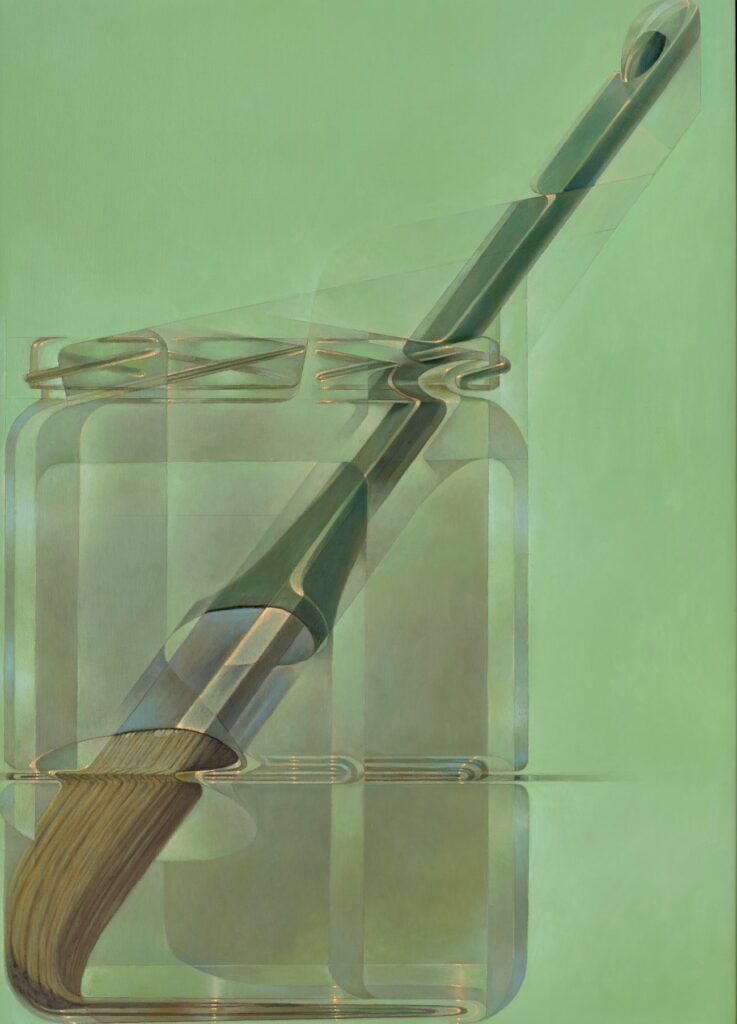

R.W : My approach is initially rather intuitive, but definitely phenomenological-analytical. That means: I start with an idea and penetrate it conceptually while working with certain themes or forms over longer periods of time. As an artist, I also see myself as a kind of resonating body that enters into a relationship with its environment and processes it in its images—one could also say: digests it. Therefore, the (visually) perceptible world is always the starting point for my images and usually clearly visible (even behind their recent abstractions). When selecting the objects for my object paintings, which I have been painting for almost 20 years, I often simply had to keep my eyes open to my everyday environment. After all, our material world consists of an infinite number of things. Sometimes I was attracted by the symbolism, sometimes by the simplicity or the intended use of these objects—Heidegger would say their “handiness” or “Zuhandenheit.” For example, you will find some tools from my studio among my motifs. But there were always several reasons, including purely aesthetic ones, that played a role in my choice: these might be the graphic form, the colorfulness of the objects, or their surface structure, which I naturally always consider in the picture. In the best case, all these characteristics were combined in one picture motif. When I have found such a motif, I proceed with the oil paint on the canvas in a similar way to a sculptor with his stone (only additively rather than subtractively), namely by roughly sketching the picture and working my way through it layer by layer, becoming increasingly precise. I have never worked from photographs for the object pictures, but always directly from observation of the object. Every brushstroke is therefore the result of an observation, either of the object or of the image. In this way, the density of the paint application becomes the sum of my observations.

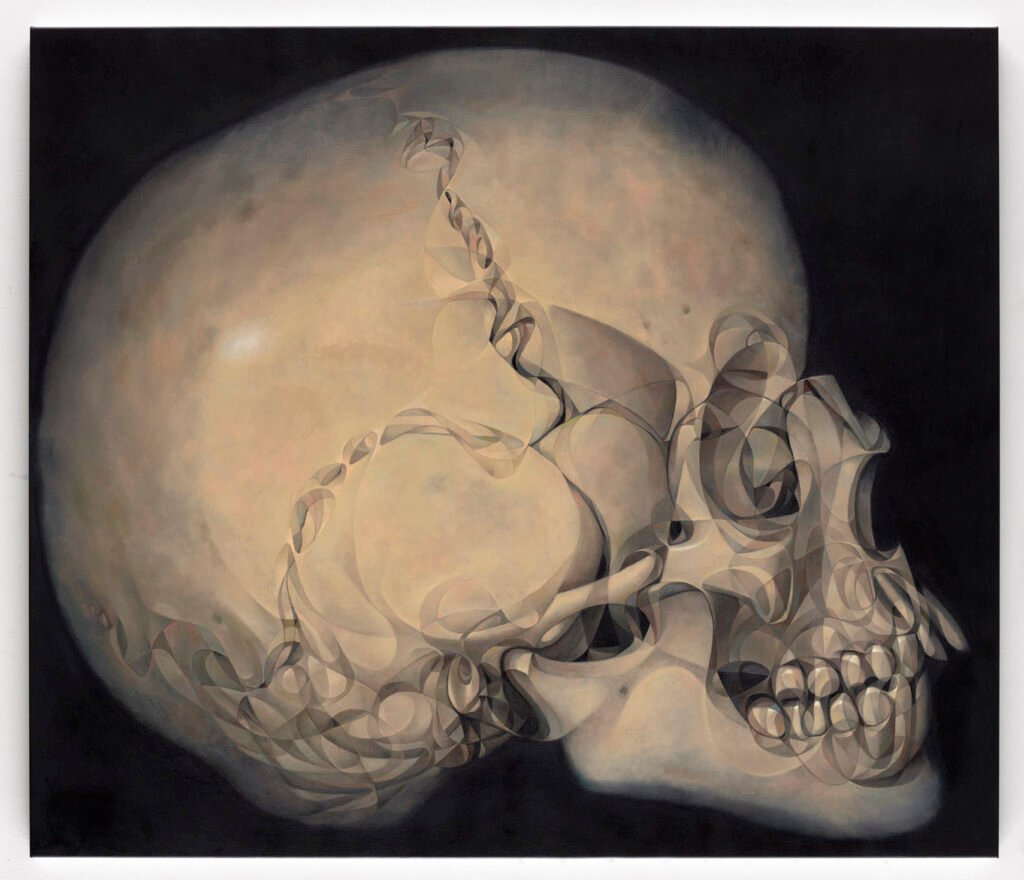

However, I have reinvented myself quite a bit in recent years and am no longer painting hyperrealistic object images, but rather abstractions of writings and pictorial icons from the history of painting. I have abandoned my former rule of not using templates because the processes very quickly take on a life of their own. Unlike in the past, my observations today are much more focused on what is happening in the image. So the images have changed, but the academic precision with which I work has remained. It is still important to me that the content of the image and the formal means used to create it fit together logically.

C.A.C : How did you experience the important turning points or moments of reevaluation you mentioned?

R.W : As I just said, there have been some major changes in my approach in recent years. After what felt like an eternity of depicting objects in a strict, hyperrealistic manner, I asked myself whether I wanted to identify with this rather narrow corset in the long term. Things weren’t going badly: art historians praised my conceptual approach, and the art market recognized my paintings as a brand and passed them on. I had collectors and gallery owners who expected these paintings. Realistically, it might have been wise to continue with this “life concept.” But I was never a realist. I always described my paintings as more illusionistic, because I find that much more exciting philosophically. I also never worked in a particularly narrative way, but rather understood my view of the world and life in a structuralist way. That’s why I often perceived it as a misunderstanding when people explained my object paintings with simple terms or tried to accuse me of a certain material fetishism with which they possibly identified themselves.

I also wanted to get away from the image of conceptual rigor. Too much concept prevents intuition. But I wanted more intuition in my processes, more room for improvisation, and I also wanted to move away from the strong focus on things in the world. I had tried a lot of things in the previous decades and knew about the diversity of my possibilities. So, without knowing exactly how, I was looking for a logical transformational process to engage as many followers of my art as possible. This began with the mundane decision to use colored backgrounds. These led to the LIQUIDS series, which now contends over 30 pieces, images of glasses filled with various liquids, in which the shapes of the reflections within the architecture of the glass have become increasingly independent over the years. I finally gave in to the growing need to transfer these freer processes to other motifs, which ultimately rendered my now old, somewhat dogmatic approach of not using photographs or projections obsolete. Today, I like to compare my painting processes to jazz music: there is a score, but within it there is a lot of room for interpretation. When I start a painting today, I don’t know what the result will be. I am more broadly positioned than I was a few years ago, and I also have many more opportunities to surprise myself and others.

C.A.C : Your painting seems to be a synthesis of several 20th-century movements—Futurism, Cubism, Abstraction—while maintaining a hyperrealistic foundation. Are there other artistic movements that have influenced your work?

R.W : I was influenced early on by modern art and the aesthetics of everyday life in the 1970s. The colors and patterns of wallpaper, record covers, and product designs were often psychedelic-abstract or concrete. Signor Rossi sought his fortune in fantastic dream worlds on television. My childhood and teenage dreams often consisted of flights or falls through bottomless abstract fantastical formations, which certainly were influenced by these visual impressions.

And although, as I said, I come from a proletarian and rather culturally deprived background, Picasso’s print of “The Three Musicians” hung above our red and white striped living room sofa. It took me quite a while to halfway understand what was going on in this picture, which can be classified as synthetic cubism, but when I did, it was like an initiation: I understood that painting did not have to serve pure representation, but rather possibilities, and that the space of these possibilities was infinite and unique each time within this narrow rectangular frame. From that moment on, I understood that making art in this society can mean individual freedom and self-realization. As a young adult, I studied Picasso and all forms of Cubism intensively, although I found Futurism more interesting aesthetically because it seemed less fixed, more playful, and more organic. I always liked the structural interconnection of spaces with objects in these paintings, which in turn created new spaces that were impossible in three dimensions. This interconnection of dimensions in the picture fascinated me just as much as the illusion of reality. I was also always a great fan of the light of Caravaggio, the trompe-l’oeuil painting of the Dutch, the Surrealists around René Magritte, and the formal rigor of Neue Sachlichkeit, which later found its way, at least formally, into the work of artists such as Domenico Gnoli and Konrad Klappheck. In the 1990s, while studying art, I discovered American art, conceptual art, and minimalism, which confirmed my fundamental approach of structural reduction of means. I am certainly not a Zeitgeist artist, but I do like to draw inspiration from current discourses: I always see painting and what I do in a broad historical context and seek a language that is, at best, timelessly relevant.

C.A.C : You have recently reinterpreted classic works such as Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog and Gerhard Richter’s Betty. What prompted you to reinterpret these icons of painting?

R.W : It just happened: Two years ago, a curator friend of mine asked me if I would like to participate in a flower exhibition at an off-space here in Berlin in 2024. I agreed. I still had a large floral still life painting from 2014, which a Berlin collector would have made available to me, but since I had already broken new ground, I didn’t want to come back with the old stuff. So I thought I could try my hand at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers, as a kind of self-experiment.

I did so and surprise, surprise: the response was very positive. And as is sometimes the case, the next opportunities presented themselves right away, because in the summer, a group exhibition celebrating the 250th birthday of Caspar David Friedrich was to take place in a gallery on the German Baltic Sea island of Rügen, which of course suited me very well. At the same time, my Berlin gallerist was considering organizing a tribute to Manet show himself—and that made three. I called them Painting Paintings, i.e., paintings of paintings. A solo exhibition was then planned for early 2025 at the Brussels branch of the Templon Gallery, and when they heard about the new motifs there, it quickly became clear: We want that too!

Well, I was a little surprised by the momentum myself, and to be honest, I still don’t know how to explain this new development to myself and others other than as a spontaneous desire. Of course, there are some interesting questions here: What do these icons have to do with me, apart from establishing a natural link to art history? Do I want to make use of their famous iconography, perhaps a little too simplistically? Although I have always worked with iconic motifs and those with art-historical references, such as the bicycle wheel (Duchamp) or my daughter’s children’s drawings.

Of course, I don’t paint motifs that don’t interest me, but here too, I’m not so much interested in the narrative side of the individual images as in the structure of their perception as historical icons and, indeed, factors of identification. It’s not simple appropriation art, but rather a kind of sampling, like in hip hop. How much of this icon is actually left in my painting, and how much of René Wirths is already in it? Of course, this can also mean: How much of these icons was already in René Wirths before? What does authorship mean here? Isn’t it much more about HOW it is depicted than WHAT is depicted? Are these interpretations at all, i.e., my abstract view of these icons, or am I rather imposing my “style” on them? These are all questions that are still unanswered for me, and perhaps they cannot be answered definitively, but they are interesting and I am personally opening up whole new conceptual fields for myself. The process of working with the levels of meaning, the surfaces, colors, and shapes is very playful. Last but not least, the results are visually very appealing. And that is what I want from a picture first and foremost: that I enjoy looking at it for a long time, whereby perception does not only take place immediately but has a lot to do with our viewing habits.

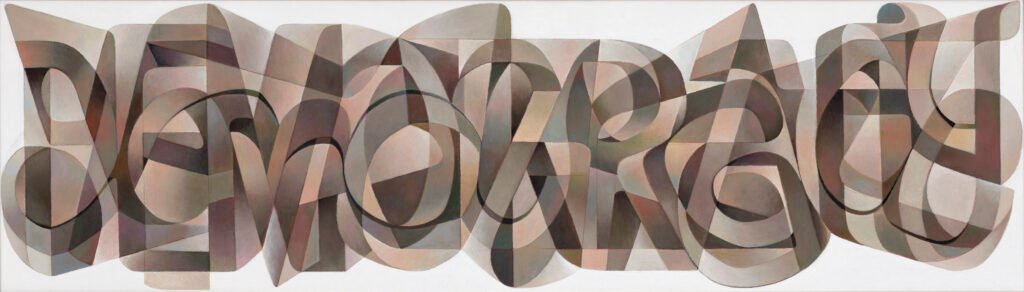

C.A.C : In your latest series, Scripture Paintings, I was particularly impressed by the typographical aspect of your work. The letters become sculptural, almost architectural forms, constructed from volume and interwoven perspectives. There is even an optical effect that is sometimes reminiscent of the legacy of Op Art, in the style of Bridget Riley or Victor Vasarely. Can you tell us more about this series and what you want to convey with this fusion of text, volume, and abstraction? Your works often feature volutes, loops, and overlays of translucent geometric shapes that create a kinetic, almost hypnotic effect. How did this visual approach develop in your practice?

R.W : The Scripture Paintings developed in parallel with the Painting Paintings. I wanted to add another pole of diversity to my work. In addition to engaging with the historical heritage of painting, I was looking for a timeless field in which I could indulge my interest in and need for language, structure, and philosophy. For a long time, I avoided using writing in my paintings unless it was part of the motif. But after the painting processes of my pictures had become so liberated from the motifs and my pictorial vocabulary had reached such an independent visual form, I noticed that I could use it to express things very directly and, at the same time, to obscure them, so that I could also reevaluate them. Words could suddenly become images, and images could form words. My Scripture Paintings are abstract images of world-abstracting language in written form. Aesthetically, they move between Cubism, Futurism, 1970s Op Art, and graffiti. I proceed as I do with my other recent paintings, layer by layer, in a slow evolving process except that my motif is simple block letters on the somehow intuitively rasterized structure of the image. The result appeals to our visual perception and our intellectual capacity for abstraction. It is equally important to me that this happens on a pleasurable visual basis that is capable of appealing to as broad a section of the population as possible. I would like to see a low-threshold approach to the perception of my images: children should be able to access them just as easily as philosophy professors.

C.A.C : Are there any formats, objects, or themes that you have not yet explored and would like to explore? What are your current or upcoming projects?

R.W : I am currently preparing an exhibition for the end of the year at the Haas Gallery in Zurich, where there will be one or two object paintings, some new painting paintings, and a few scripture paintings on display. Otherwise, in the medium term, I plan to occasionally incorporate biographical photos from my childhood. For me, this raises the question of how much of my history I actually want to reveal and whether and how I can manage to turn supposedly mundane or at least ambivalent memories into visually exciting images. As I said, I’m now always open to surprises.

Site web © 2025, Double W studio ༶ Tous droits réservés

Site web © 2025, Double W studio

Tous droits réservés